In CoHERE, we are exploring the differences in how people across Europe represent their heritage and identity. The projects explores how heritage can lead to common ground with others, but in the increasingly hostile and tense climate - from religion to EU exit politics - heritage and identity can twist, undermine and break relations between culturally diverse audiences.

Specifically, "Talking Mechanisms" highlights some unique and alternative approaches to design research on how to spark, stimulate and nourish dialogue on heritage-identity among different people.

What 'resources' do the different parties use in maintaining conversations? Can new kinds of creative digital interventions facilitate conversational behaviours and new dialogues among culturally diverse audiences?

As part of our primary objective of Year 1, we explored processes for designing creative-practice interventions that foster and sustain dialogue on heritage and identity.

In order to understand better how heritage-identity is expressed and how meaningful dialogue can be opened and sustained, we conducted people-centred design research - with an especial focus on mechanisms for talking, on mechanisms for talking about heritage and identity, and finally on mechanisms for talking about heritage and identity among different people.

As you will see in the corresponding videos, we made three studies with different foci -

1. Dialogue-specific - zooming into the particular question of how dialogue is opened and sustained -

2. Design-research tools - prototyping possible resources for generating and sustaining meaningful dialogue on heritage-identity

3. Workshops - testing and consolidating tools (of #2), and applying them to a specific group of people and topic

Work-in-progress site for documenting the workshop materials.

DIALOGUE-SPECIFIC

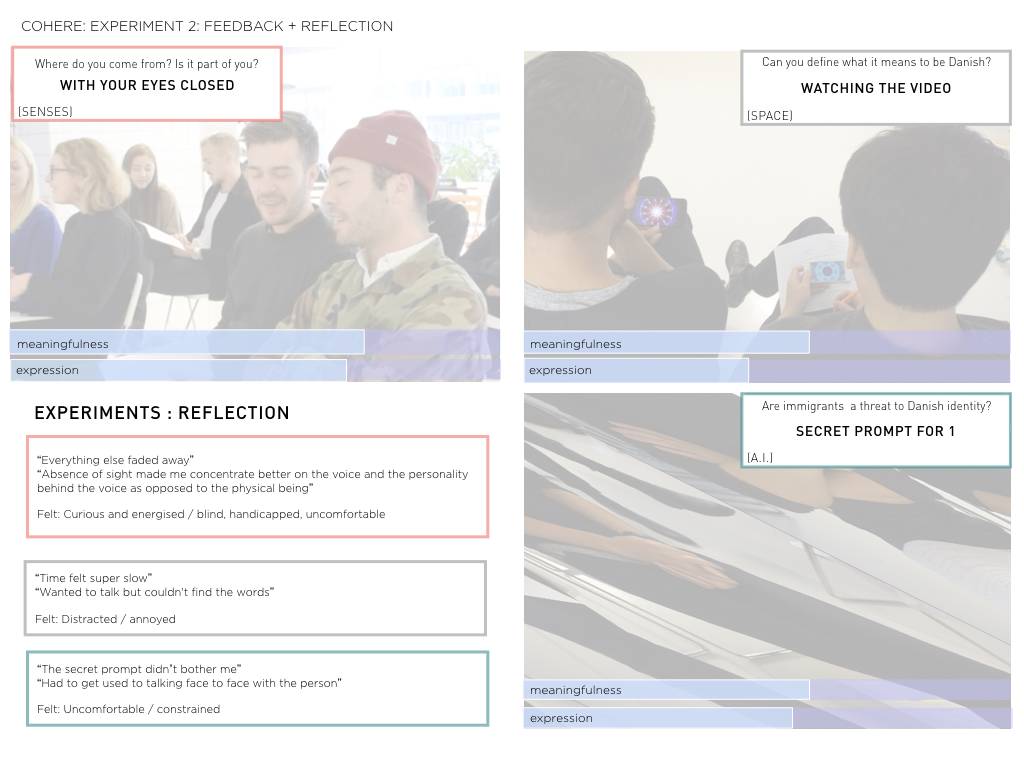

As our work takes dialogue as one of its most salient goals, we began by studying the conversation and dialogue from an analytical perspective. In our initial experiments, we considered dialogue when it is one-on-one and, face-to-face simply to understand how certain rules and structures shape this most analogue form of exchange. During our desk research and expert interviews, we noted the importance of structure in dialogue, and designed a series of experiments to isolate and examine rules that set, guide and restrict dialogue in a person-to-person, face-to-face environment.

We call this the very “inside” of any dialogic experience - that is, the act of talking and listening.

Here we ask - how do various sensual constraints impact communication? What happens if you cannot use your voice to communicate at first, and then 6 minutes later, you are again allowed to use it? Does closing your eyes necessarily lead to a decrease in understanding? Or might such isolation of a sense (just hearing) actually improve our ability to focus and listen more carefully?

We conducted experiments to test these dialogue-specific questions, creating experiences to learn more about the effect of these constraints. These experiments took place at:

1) An open-house design event at the Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design (Copenhagen, Denmark) where we conducted sessions with 6 pairs of individuals, where each individual was from a different country and none of them knew one another previously.

Experience + feedback:

2) A workshop at Space10 Future Living Lab (Copenhagen, Denmark) with 20 conversational design experts, approximately half of whom knew one another previously.

Experience + feedback:

Though rules such as “make no eye contact” or “no voice, only face and body expression” often frustrated participants, the relief and increased attentiveness upon return to full expression became a key insight for our design of dialogic mechanisms and tools. That is - to design experiences that guide participants through different modes of expression and abstraction of communication and dialogue - physical, verbal, written, craft - as opposed to relying on one sole form of communication as the only mechanism for dialogue.

We also learned about timing, patterns of body language as they match or do not match open expression of opinion, level of depth of information needed around a given topic, and people’s willingness to enter into a discussion - even without a goal of conclusion - if they have a time restriction and direction to start.

DESIGN-RESEARCH TOOLS

After this focus on mechanisms for communication, we opened up the next arc of our inquiry to the overarching context of dialogue about heritage-identity, and probed how we might support dialogue specifically about heritage-identity through design methodologies.

We ran interviews and co-design sessions to uncover insights and potential opportunities for the tools we would use in our next workshops on dialogue about heritage-identity in Europe.

We wanted to understand what would bring out, nurture and sustain dialogue about sensitive topics and difficult histories, the critical aspect of heritage as it mixes with identity.

A. Interviews

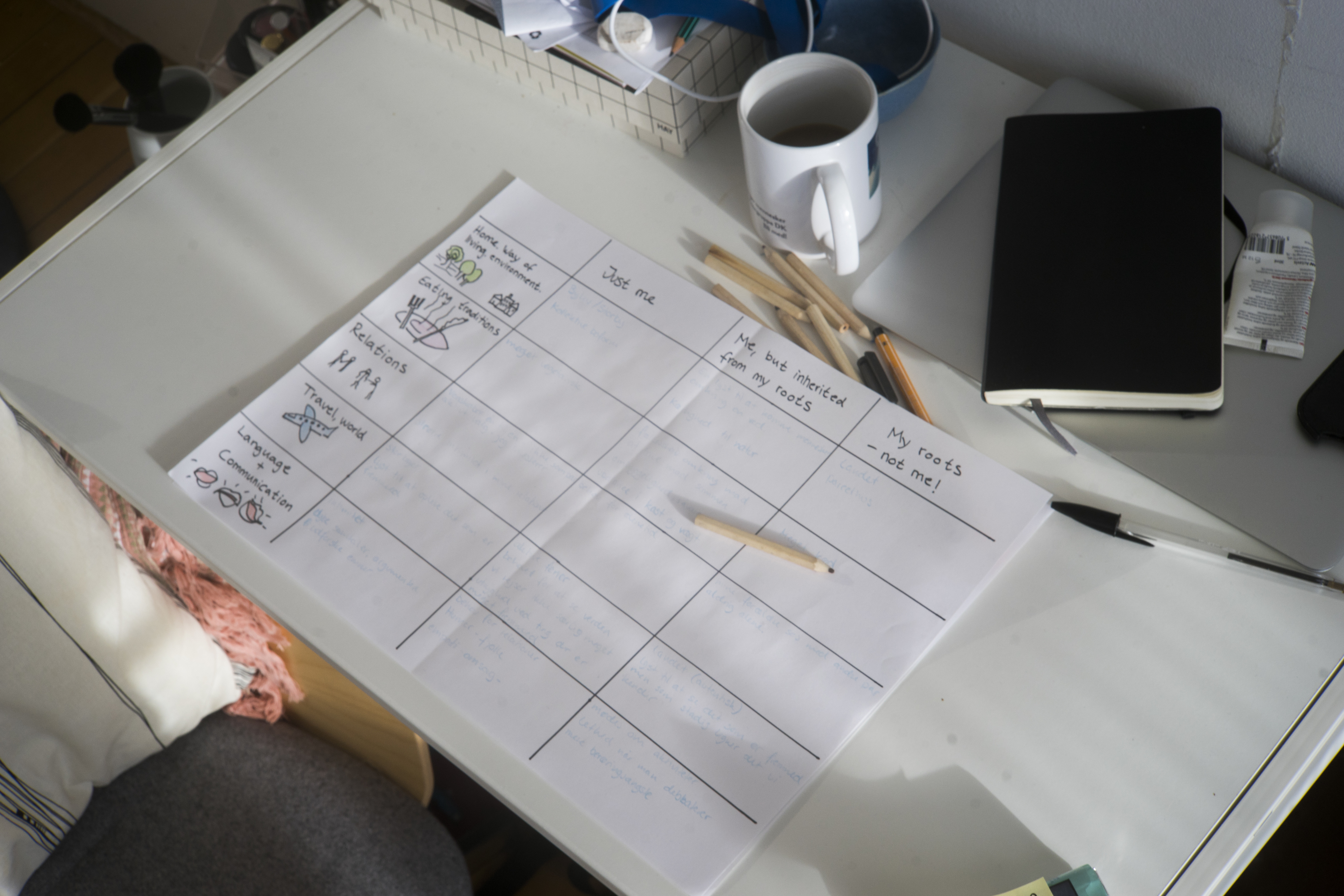

We interviewed 15 individuals from a variety of backgrounds, though all living in Copenhagen and identifying as European. We brought various paper-based tools to the interviews to generate discussion. Given our desk research and early tests, we knew that varieties of expression from tool to tool and within each tool might be crucial to encouraging different types of participants to express their notion of heritage-identity. Thus, we made some tools that were as open as “make a map of your world and mark it according to how “at home” you feel in each area” and some tools that structured participants’ input more strongly, such as what are “elements of your life that are just you / you and your family / just your family.”

We found that the tools were useful not only to bring out important markers and themes for the Europeans we interviewed - but also to stimulate and automatically document their own perspectives and inner-dialogue.

For example, one design research tool that we used was a timeline for the interviewee to place events that were important for them, for their family and for their country. This tool engaged them to consider what it means to be Danish vs. European, how much they do or do not identify with their “mother-country” as opposed to the country where they live now, and how they do or do not engage with the political controversies that they themselves often brought up as part of that timeline. As part of the same exercise, we asked the interviewee to make a map of notable places for them, their family and their nationality - noting places where they feel “at home” vs. where their family feels “at home.” In these markings, the interviewees uncovered and then discussed notable tensions between their personal perspective as opposed to their fellow country-men’s perspective.

B. Co-design

Finally, in our co-design sessions, we engaged in a lengthy and circular, self-reflexive exercise with a small group of Danish students who are approximately aged 30. The students first interviewed themselves about something in their lives that represents their own heritage-identity, then made their own tools to interview older relatives and similarly-aged friends on the topic of heritage-identity.

Then, with observations and insights from the interviews in mind, the students came up with concepts for an interactive installation that would invite the public in to experience and create artistic content (visuals, sound etc.) that reflects upon heritage and identity.

This overall arc not only generated insights for us in terms of designing our own tools for interviews and workshops, but also, the participants found that following this design-research process was in and of itself a TOOL to help them express and explore THEIR heritage-identity.

Through this gradual layering of dialogue and then dialogue on heritage-identity and finally dialogue on heritage-identity in Denmark we have gathered key insights to base our further iterations of public-facing tools and experience designs.

Interview tools with inputs:

Matrix representing what you share and don't share with your family:

Map of where you feel at home:

WORKSHOP

After focusing on the most inner piece of dialogue, then applying that focus to extend to dialogue on heritage-identity, we took the step of narrowing the audience as well as overall topic. With this narrowed context, we then re-designed, refined and iterated tools and concepts we had generated in earlier stages (when focused on dialogue and when making interviews). We hoped that the workshop would help us to gain greater clarity around the principles of dialogue we have put forward and how they work when identity and heritage come into negotiation.

The workshop's topic was chosen with the following goals:

- Provide opportunities for expression of different viewpoints

- Open and ambiguous enough to allow people with different backgrounds to bring their own perspective

- Able to be used as an overarching topic in multiple contexts

- Specifically relevant to the European context

The workshop's experiences were designed to support the following goals:

- Openness and civic listening - everybody has the right to contribute and to be listened to

- Tension or conflict - provide a setup where tension is explored in a productive way

- Perspective- taking and reciprocity - participants will encounter perspectives dissimilar to their own

- Transformation - the activities will record change and transformation

The small workshop was held on February 24, 2017, for 8 participants in Copenhagen, Denmark as shown fully in the accompanying video.

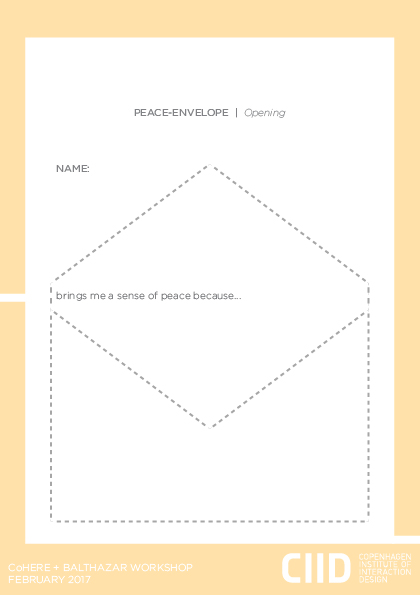

The topic of the workshop, as informed by the key points above, was about personal understandings of peace. We were curious to unearth how peace is defined and represented across generations - specifically in Denmark, where each generation may have experienced notably different definitions and understandings of peace. The participants were recruited across two age brackets, where four participants were over the age of 65 and four participants were under the age of 40.

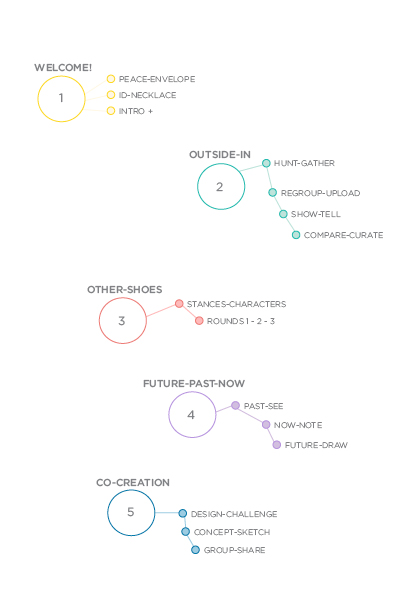

We designed a series of five experiences, including the introductory exercises, where each experience focused on one or more of the goals we sought to explore and had the potential to be re-designed for a different location or physical context.

Each of the workshop's five experiences is shown through the accompanying video, but three aspects of the overall day are relevant to highlight.

1. We designed this series of experiences with different compositions of groups - whether pairs or foursomes, full group or half group. Varying the composition meant the participants' feedback at the end of the day was not solely based on their personal experience of a positive pairing, but rather reflected the overall experience (though of course impacted by the social nature of the workshop).

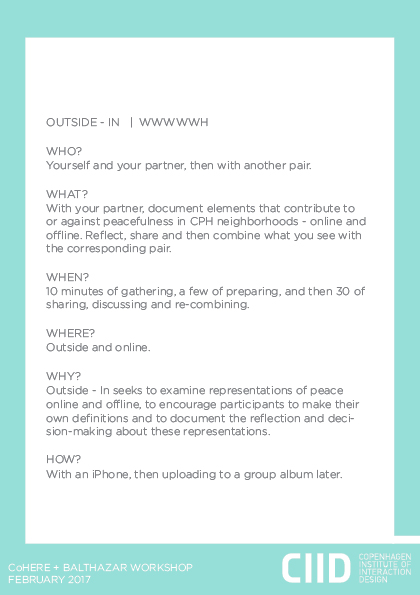

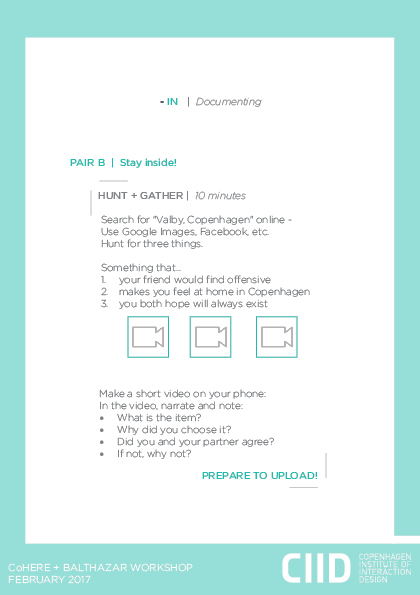

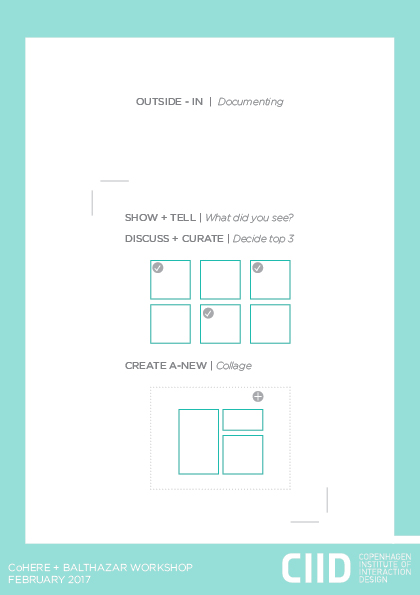

2. Furthermore, we designed the flow of the day such that we were weaving between experiences that included technology or not. For example, the first major exercise, "Outside-In" asked participants to use their smartphones to collected representative images to answer a series of questions and then share, compare and curate answers as a small group. The second experience was face-to-face, with prompts and structured rules through simple cards. The third experience incorporated an intimate VR experience of a series of videos showing riots and protests in Copenhagen. The last experience was a co-creation exercise, again using only cards and paper.

In this way, we sought to use technology when and if it made sense. For example, the VR experience gave each viewer a focused and specialised sensation and space of time to consider a piece of audio visual footage. This visceral experience would have been hard to communicate as effectively through photos on paper or words only. Furthermore, it allowed us to test and collect footage-data about how different people (whether older or younger, from different parts of the country) perceive the same act (a riot in Copenhagen) differently - because of the questions the non-viewer was required to ask of the VR viewer. In this way, we also tested the potential for a Socrates-style learning and expression through asking Socratic questions as well as a "sensory-constrained" element. as the non-viewer could only "see inside" the VR experience by probing questions and imagining visuals before they themselves could then view inside.

The "Outside-In" use of smartphones to document surroundings allowed part of the group to go outside and bring what they saw back inside to share and compare with what the "inside" group had found online - both were searching for answers to the same questions, but one searched online and the other searched "offline" - as in, physical space, outdoor surroundings.

The participants - though varied in age - were able to use the technology-based tools for experiencing and expressing themselves. Furthermore, their inputs - specifically for the "Outside-In" experience - caught their voice as well as decisions in the moment, thus serving as data for the researchers to easily follow up on after the fact.

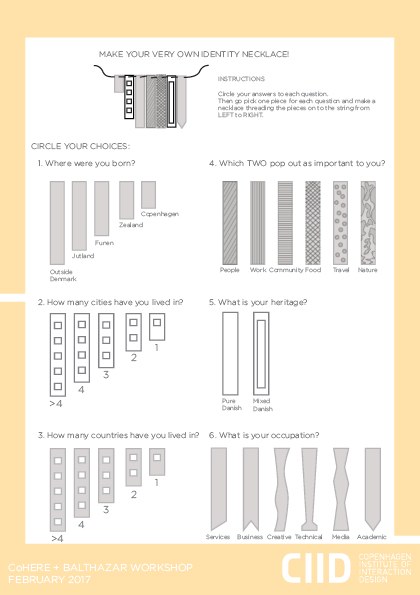

3. We used knowledge gained from the structured dialogic experiments as well as the previous interviews and co-creation workshop - pulling out the key inputs and feedback to design the workshop for February 24. We prototyped slightly more standard design research tools such as probes/priming objects, as well as unusual warm-ups, such as creating a necklace to represent one's identity based on a series of questions and pre-laser-cut pieces custom-designed by CIID.

A few insights that drove these changes:

While objects and images from the past play a strong role in individuals' memories, they were also eager to remix or re-represent these elements in new ways (from interviews and co-creation workshop, led to "Peace-Envelope" and "Outside-In").

The involvement of participants in co-creation exercises itself is a tool in generating, nurturing and sustaining provocative discussion on heritage-identity (from co-creation workshop, led to "Co-Creation" segment).

Rules to structure body language, roles and sensory expression can enhance and sharpen a dialogic experience (from experiments and interviews, led to "Other-Shoes").

OVERALL

In each of these experiences, we sought to better understand the differences and similarities among individuals, how they brought their heritage-identity to the tensions in their different answers, how they negotiated discussion and answered prompts without necessarily knowing their interviewer, partner or group well. Going forward, we seek to design for and engage with topics and groups that would have a higher likelihood of experiencing challenging and tension-full dialogue, and to understand better the potential for digital-specific interventions in terms of asynchronous and off-site communication.